What Are The Main Types Of Brake Pad, And Which Is Right For You?

As you all know, a car’s stopping power can be just as important as any horsepower figure or torque output. When you’re going for a weekend hoon and approach your favourite string of corners, you want to have full confidence that the application of your foot to the middle pedal will create a corresponding braking force.

At the same time, there is only a certain amount of stopping force that your brakes can create. Brakes are specced taking into account a vehicle’s weight and power, with the aim being to create enough force to fully lock up all four wheels, overcoming the torque of the spinning brake disc. From there on in, it’s then down to the tyres to produce the required friction force to bring the car to a stop. So there’s no point in having race-spec brakes coupled with some cheap recycled street tyres.

To maximise the grip that the pads can have on the rotors, different materials can be used within the pad compound to match the braking and temperature demands. In the end, the figure that matters most is the coefficient of friction between the brake pad and the rotor, as this is the main factor that converts the kinetic energy of the spinning brake disc into thermal energy, otherwise known as heat.

The retention of that heat energy is governed by the thermal conductivity of the material. Brake pads have specific operating temperature ranges, and constant hard braking can result in the pads overheating if they can’t dissipate the heat to the surroundings quickly enough, therefore a high thermal conductivity is required.

To put all of that into perspective, here’s a quick run-down of the different types of brake pads, looking into the characteristics of each to help you pick the right material for different motoring scenarios.

Non-metallic (organic)

The softest form of brake pad, non-metallic pads are made up of different combinations of glasses, rubbers and resins like cellulose along with a small smattering of metal fibres that are all manufactured and cured to withstand a substantial amount of heat. The composite that results is relatively soft and therefore wears away quickly, but is easy on brake discs. This makes them poor for anything other than daily road driving, and even then a more metal-based pad is preferable to avoid frequent replacement.

The accelerated wear of organic pads results in large amounts of brake dust covering nearby components which can also become a bit of a pain. Originally constructed from Asbestos (due to its talent for dissipating heat) non-metallic pads were swiftly switched to other compounds due to the health and safety issues revolving around the toxic material once airborne.

The nature of the new compounds mean that this type of pad should only really be used in applications where large brake demands are rarely needed. Purely organic brake pads can be found that use rubber or glass composites but they wear out quickly if used regularly. Kevlar pads are the expensive alternative - being six times stronger than steel - and provide far less performance drawbacks for an organic pad.

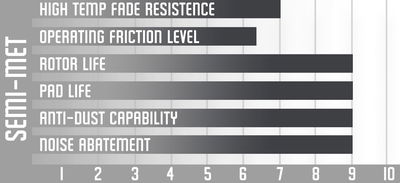

Semi-metallic

These are found in the majority of cars being sold today. They use a combination of both synthetics and metals to form a predominantly metallic hybrid compound. Once the material of the fibres has been chosen, they are bound together using an organic resin. They are then moulded into pre-set shapes and baked in a furnace for three to five hours to enhance their durability.

The metal element to the compound makes them more resistant to heat and wear than the purely organic variants, but as metal has a lower friction coefficient at low temperatures to the more pliable synthetic material, a tad more pedal power is needed to create the same braking force with the semi-metallic pads when cold.

Adding more metal to the compound (around 60 per cent) can make metallic pads suitable for heavy braking situations where longevity is needed over the presence of organic material. This high spec is perfect for performance cars and heavy vehicles that constantly need large braking forces to wick kinetic energy from large rotors rotating quickly due to high torque inputs.

Typically made using either sintered steel, graphite or iron, semi-metallic brake pads have a high thermal conductivity and – when combined with proper brake ducting for cooling – can be everything a high performance car needs to cope with, even on the most intense of track days.

Ceramic

But if a set of steel pads still leads to brake fade as overheating sets in, then maybe shelling out for a set of full ceramic brake pads is worth it. Confined to the most expensive of supercars due to the sheer expense of manufacture, the ceramic compound used in these high-spec pads is exceedingly good at absorbing heat generated from very hard, continuous violent braking.

This means that they can continually recover from whatever demands are placed upon them, even in such events as endurance racing. This feature however makes ceramics difficult to warm up to operating temperature which can prove a hindrance for daily driving.

The use of clay within the ceramic gives these pads the benefit of the high coefficient of friction of an organic pad when cold combined with the strength and durability supplied by the presence of a small percentage of copper moulded into the compound.

Every type of brake pad has its downsides; organic pads are normally too soft for general use, metallic pads are very hard on brake discs and create more noise and dust and ceramics are catastrophically expensive, along with taking forever to heat up. But the choice of what compound to go for all comes down to the application.

For example, having high-temperature steel or ceramic pads on a street car would be wasteful considering the pads will rarely – if ever – get up to their optimum performance temperature. Then again, if you were to undertake some serious mountain or track driving with stock metallic or organic pads, you’d risk them overheating and making that brake pedal feel frighteningly long. In sprint racing, coefficient of friction is priority, while in endurance racing, longevity is paramount without throwing frictional properties out the window.

Brake pad manufacturers will often give a range of pads suited for every application. EBC, for example, use a colour-coded system, with Greenstuff pads increasing braking performance by 15 per cent when compared to an average stock pad, Redstuff pads adding a ceramic element for fast road cars and then minimum-fade Yellowstuff pads used in performance cars that find themselves on a track day now and then. Other manufacturers like Tarox will provide similar compound varieties using names like strada, corsa and track for you to choose from.

Changing your brake pads to something a tad more performance-orientated can be a simple and cheap modification to bring your car’s stopping power in line with the driving force under the bonnet. But with countless factors like rotor interaction, thermal conductivity and usable coefficient of friction all coming into play, it’s worth doing some research into the exact spec of compound that is usable for you. Brakes – like tyres - are an area that should never be neglected. So when you finally decide to go on that epic road trip or to track your car for the first time, make sure your pads are up to the job.

Have you changed your brake pads recently? Have you upgraded the compound to something a bit more track-biased? Comment below with your brake pad setup!

Comments

my favourites are made with silicon carbi….. sorry i meant silicon carbi… oohhh

“Being able to stop quickly is much more important than acceleration”

Tell that to the hot rodding community 😂

There are a few hot rodders that will agree with that statement, but usually only after they have to build a second car when the first one didn’t stop.

At the moment im running Autozone Ceramic pads that were in the trunk of my 03 Galant when i bought it. I plan to save a little and install Evo front brakes, since they are interchangable. I will probably use semi metallic pads and maybe high carbon rotors.

Out of curiosity, are ceramics ideal on heavy vehicles like trucks and buses that are constantly braking? Would it help with brake fade? I feel that if you look at it from a scientific perspective it would make sense, because supercars= very light weight, but high speed, heavy vehicle=lots of weight, but less speed, so the momentum when it is calculated should roughly be the same. Any ideas?

Awesome article! I find it extremely useful. Keep Posting.

Great Post, I find it extremely helpful. Keep Posting.

http://www.toughla.com/portfolio/lcv-products/

Pagination