Here’s How Game Developers Create Virtual Race Tracks

When racing around tracks from the comfort of your sofa, it’s easy to forget just how much effort, time, resources and energy goes into creating these loops of pixelated perfection.

Most gamers never even think about how a real-world track gets transformed into a virtual version. They’re more likely to be thinking, ‘am I going too fast to make this corner’, and ‘no matter, I’ll just use the car in front as a brake’.

The creation of the circuits, then, doesn’t get much attention, but it’s one of the most important elements of a racing game. We caught up with Slightly Mad Studios COO Rod Chong to find out just how the tracks in Project Cars 2 got created.

It’s a long and detailed process, which he’s broken down into five phases for us.

Phase one: pre-production

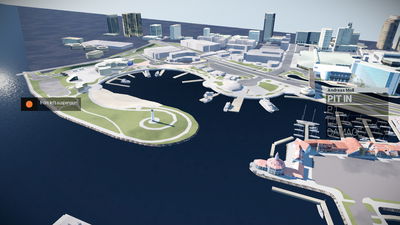

This initial phase takes a huge amount of resources and time. Rod said that it takes a group of four people four months to create a ‘normal track’ (Brands Hatch, Donington Park), and six for a city circuit (Long Beach). Here’s his explanation of phase one:

“To start with, there’ll be a lot of discussions on what we want to include. We’ll often look at what the community requests are and also look at what types of racing we are going to showcase. Obviously with Project Cars 2, we have rallycross as a key new type of racing. So, we’ll look at that, see what the most famous and iconic tracks are. Or, we’ll look at, say, our love of classic and vintage car racing. So, we might choose some more retro tracks from the past.”

A fascinating element of starting this phase is the licensing process, because car companies have licensing departments, but tracks don’t. So, Rod says it’s tough getting in touch with circuits sometimes and receiving responses. So, the developers have to massage their motorsport contacts to find the right person to chat with. Once a dialogue has begun, the planning can start.

“In general, you need to scan a track. That’s the best way, you can look at these realistic racing and simulations games as a bit of an arms race between us and the other racing game titles.

“The standards now in racing games are you have to laser scan the circuits, or we have another technique called drone photogrammetry, where you fly a drone over and it takes several thousand photographs in a grid pattern that’s automated from several heights. Then, you put these photographs into a computer to produce the geometry and texture.”

Afterwards, the next stage is to send a crew to the circuit - where they’ll walk around it, take several thousand more photographs (of shrubbery, grass types, kerbing, buildings, things like that). A little tip from Rod is to take pictures of objects at 90-degree angles, so the developers can recreate it for the geometry. Snapping things in different lighting conditions is also a good idea, as PC2 has 24 hours of lighting.

“Data processing is next. You have to generate point clouds, which come out of the laser scan, or photogrammetry data. That all converts into a high-detailed mesh. From there, you also have to do data processing on the outer terrain as well. Sometimes we have geodata of the surrounding hillside and mountains. We have to build this too. Everything has to have millimetre accuracy.”

As you’d expect, the opening phase is a pretty mammoth task, and Rod also added how crucial the track visits are for the developers, to get a first-hand look at all the details in person, and see how things change with different weather conditions and seasons.

Phase two: core track creation

“The first part of this next stage is to create the ‘loft’: the actual track surface that will be used for driving. What you do is follow the laser scan, point cloud or the drone photogrammetry scan, and we’ll end up creating the actual in-game loft by hand. It follows the data that’s been collected completely accurately.

“Usually we do a pretty basic loft, export that and get it in-game. At the same time, you’ll have other artists working on the landmarks and key buildings, as well as inter-terrain creation - pitlane, access roads, paddock areas, gravel traps. All the areas the car may end up driving over.

“From there, you have to build all the kerbs, run-off areas and other stuff, and set up the physical environment. So, putting in the surface properties – if there is a gravel trap, the game needs to know it’s a gravel trap. The properties are tagged so the game engine knows to tell the physics engine that’s a gravel trap, and triggers the correct sounds too.”

The material properties are also put into the game too, so car handling responds to the physics engine. Track boundaries, safety fencing, tyre walls and barriers are added at this stage too, plus outer and distant terrain, secondary building structures and props. So, the look of the track starts to take shape.

Phase three: track detailing

While this is the one that requires the least explanation from Rod, it’s all about fine-tuning and adding in the smaller but equally important elements that turn it into a proper virtual race track.

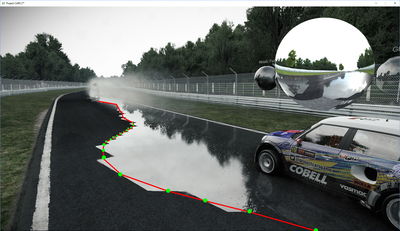

“We create the side roads, texture overlays, painted lines and things like that in this phase. All the textures, so different types of grass, are built and added. This is also where the Live Track 3.0 (dynamic weather system) is set up and tested, making sure the tyre marks, drying lines, dirt and other elements build up organically with the changing climates and weather.

“They have to be technically set-up, alongside the seasons and seasonal variations in the game too. We also have to work on the grass – add the weeds, small bushes, all the tiny details like that. Everything’s done by hand, which is why it takes so long. We also have to do the pitlane and garage details as well, as that’s somewhere gamers spend a bit of time.”

Phase four: level design and population

“From here, we have to start putting in the data for the AI drivers. This means setting up the grid, so the cars know where to populate it. Also for the garages and pitstops, the AI and player cars need to know where they’ll be stopping. The replay cameras are also added into the game and we usually follow what’s done in real life for those tracks.

“There’s also figuring out where to put the dynamic and destructible content – cones, advertising boards, bollards, anything you can hit, basically! And trees… a lot of time is actually spent on trees and bushes. To add all these geometries in but still maintain 60 frames per second is a bit of a challenge.”

The people are also put into the game at this stage, and they’re all created by hand. Rod says it’s worth noting that when you race at a track in the winter, the crowds are wearing different things to when they’re there in summer. It’s all in the details!

“Then, there’s also trackside cars, busses, emergency vehicles. The lights also have to be added as well, plus the animated assets – the video screens, helicopters, flags, things like that. And the lights for night racing too. The race day stuff is also put into the tracks at this time (pit equipment, motor homes, team trucks). Finally, you add all the track sponsorship. Sometimes you have to talk to the tracks because they want to only put in real-world advertising, but others don’t really care.”

Phase five: final polish and optimisation

It’s almost done, the track is nearing completion and, at this stage, it’s nearly ready to be raced.

“So, here we have to set-up the location-specific weather. If the track is in California, what happens in winter is very different to a track in Italy. All these things, we have to work on - what’s the lighting like, what’s the feeling like if it’s in northern Europe or Australia.

“There’s a lot of different lighting conditions and visual styles depending on where the track is in the world, and also the climate, because we have a full simulation. Then, we have to go in and see how the track looks, and calibrate things. This is where we check and make sure all the different elements and textures are balanced.

“Level of detail settings is another thing we leave to this phase. If you’re using a big, powerful monster of a gaming PC, you can jack those settings up. If it’s older or a gaming laptop, you’ll have to turn some of the graphical settings down. So, we have to prepare the tracks to work with different types of settings – as there’s different levels of detail. The same goes for the level of detail that goes into a console version compared to a PC version of the track.

“From there, we have to optimise the geometries. Then there’s bug fixes, a QA pass to make sure everything’s working correctly. Finally, the last bit is showing the track to the original owner to sign it all. And there we have it, a finished racing track!”

Quite a bit of work, right? It’s amazing to hear the stages of creating a race track for a video game broken down like that, and definitely makes you think more about how the video game was built and developed.

So, when you’re trying out the Long Beach street track in Project Cars 2, or flying around Lydden Hill in a rallycross beast, now you know what the developers at Slightly Mad Studios have been through to get that specific location to where it is.

Comments

Cant wait for pcars 2

AI settings for the track.. I think the creators of FM6 never heard of that…

I love the drivatards, especially when you turn aggression on. Just like racing online!

What if AI worked like those neural evolution videos you see on youtube

TomislavCelić#CTthegame

Thanks for the tag

Need for Speed haters.

I wanna see you try to make a game.

K hold my beer

Computers,computers are the answer!

Always wondered how they done this, pretty neat

Thanks, I definitely learned a lot doing the interview and writing it 👍

And…. All this goes to waste when I get lagged 37,000 feet into the air :(

Hiw do i make a post on this thanks

As a game dev

I APPROVE

It was fascinating during development of the first game watching tracks develop stage by stage. Driving Bathurst when it was just a loft hanging in space then seeing it evolve into the finished product was amazing.

Pagination